Earth Day in San Diego. A wonderful and wacky blend of concern for the earth, making a

dollar, and having a good time. It’s a good symbol, too, of American ingenuity and

generosity.

But what happens when this kind of enthusiasm travels just a few miles south across the

border into Mexico, and tried to do something about the poverty it finds there? To find

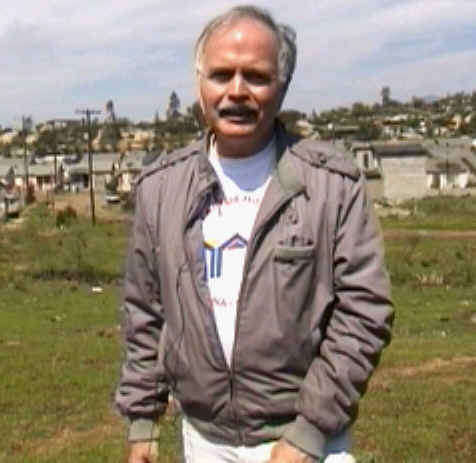

out we talked with Skip Fralich, a solar engineer and long-time worker for Habitat for

Humanity.

Skip: I’m Skip Fralich and we are at Tecate, Mexico on the border of the U.S. and

Baja California, Mexico. This is a site where we’ve got 40 Habitat for Humanity

families. The project started about 4 years ago in partnership with the Mexican government

and Habitat for Humanity. This all started with a gesture from a Canadian person who had

some lumber he wanted to donate for homes, and arranged to have it shipped here to build

these 40 homes.

Habitat for Humanity and the Mexican branch of the government called Immobiliaria

planned this project together and it was intended to be roughly a 50-50 partnership

financially. Immobiliaria would provide the land, site preparations, and the utilities:

electricity, water and sewer, and Habitat would provide the volunteers and the materials

for the home building, along with the families, themselves.

Habitat for Humanity provided Immobiliaria with criteria for family selection along the

lines we used in the United States and in other countries of the world, and Immobiliaria

then selected the families. At the beginning it was designed so that nobody would know

which lot was theirs so that everybody would be working together, helping each other out,

build all the lots up equally – 40 lots total – and then at some point when the

house was habitable, then there would be a lottery and the families would get a house

based on that, then move in and do the interior work. The families were contracted. They

would each sign an agreement to put in 750 hours of time, and they would pay $3,500

equivalent U.S. money to Immobiliaria for the land and the utilities, and $3,500 for the

house. That $3,500 for the house would go to the Immobiliaria, but it would then be

redistributed once they formed a Habitat chapter here locally, and it would go back to the

Habitat chapter for building more homes. The families are paying roughly about $100 a

month to pay off their debt with zero interest and zero profit over roughly a 5-year

period.

Jim: The fundamental goal was reached: 40 families now live in their own homes, which

is something that might have been difficult or impossible to achieve without this

partnership between Habitat and the Mexican government. We talked to some of these

families about how their lives had changed.

Man: Before living here I lived in Colonia Militar for 20 years and paid rent. When we

started there were about 80 families, and from the 80 families only half would get houses.

There were many families and few houses. When we started to work, those who stayed were

really interested in a house. Many said, "A lot of time working and only a few

houses," and they kept leaving until we were left with a group now living in the 40

houses. We had the idea we wanted to build the very best we could so that our house, no

matter which one, would have no defects.

Lady: We lived in the dining room of a factory for 9 years, 5 children and 2 adults. My

husband was a night watchman and also a factory worker.

Question: How did you feel when you got your house?

Lady: I felt freed and very good because this was going to be my own house.

Man: I felt very good, and it is very different from when I was paying rent. There were

a lot of problems. It is very pleasant and quiet here.

Man: The problems came from the conditions created by the landlords. The service was

very bad, and the rent was high. This house is the result of our labor. To have our own

place is worth the sacrifice we made.

Woman: We plastered, we did the electricity, the bathroom, the plumbing, we made the

floors, all this. We stuccoed the houses, painted, everything.

Question: Did you like it?

Woman: Yes, I liked it. It makes it more valuable.

Jim: Even now Habitat continues to work in Tecate in partnership with various American

community and church groups.

Tell us your name and how old you are.

Girl: My name is Jule and I’m turning 16 today.

Jim: Great. Happy birthday.

Girl: Thank you.

Jim: Where are you from?

Girl: I’m from San Marino, California.

Jim: What are you doing here?

Girl: We are building a soccer field, like basketball court for the kids here, and

right now we’re building a porch for this building.

Jim: Why did you come down here instead of just taking the week-end off?

Girl: I’m with my church, and we just came down to learn about God and to help the

people more.

Jim: But with every project like this there comes a time for assessment, an assessment

that can help future projects to be even more successful.

Skip: In retrospect in terms of sustainability there are some things that I would do

differently, and hopefully we learned these lessons and will incorporate them into future

activities. Number 1, the offer of the lumber donated from Canada was almost felt too good

to be true. It was an offer we couldn’t refuse. All we had to pay was customs and

shipping, but that turned out to be a fair amount, and then there were delays in the

Mexican customs getting the lumber approved to go across the border, and then there were

the standard philosophical issue of Habitat for Humanity. Normally its policy is to use

indigenous materials, and the lumber isn’t indigenous to this area, so people are not

used to working with it. It is a fire risk, and so we had to do some extra costs to

protect the homes from fire because fire response is very slow out here. Another

environmental problem that emerged here is in regards to the sewage treatment system. The

partnership with Immobiliaria was very well-intended, and I think it is still a good

possibility, but there is some things that were not addressed as well as they could have

been here. For one, the site selection. I don’t know if there was adequate

engineering. Obviously there wasn’t as far as the water table here. During

construction it was apparent that we are sitting on a high water table, the water table

coming to within a foot of the surface during the high water seasons. The

Immobiliaria’s plans to put in individual septic tanks that would percolate would not

be adequate. It wouldn’t drain during the high water season.

The Jimmy Carter project in Tijuana in the summer of 1990 was quite amazing as

phenomenally 100 homes were built, 80% complete in 5 days, and some interesting problems

and situations developed there. I think, number one, the idea was benevolent to build 100

homes, but in a way paternalistic. We tend to move in and try to do grandiose things and

do them fast in a Type A construction manner, where in the long run I think it is

important to have a lot more careful planning, family selection, a family acculturation to

the concept before you launch into the construction project. In the Jimmy Carter project

we had over 1,000 volunteers in pitched tents, Jimmy and Rosalind Carter along with them

for a week on a hillside, and it was quite exciting, very emotional, everybody worked

hard, it was spiritually rewarding, the families were selected kind of late in the

process, and some of them were even selected during the process of the construction blitz.

They were given homes, told to go join the American volunteers, and build their home.

They, of course, did that. In the aftermath there were some issues that were confusing

among the families and caused some animosity among parts of the community. Sometimes they

didn’t understand that this was their home. They sometimes saw Habitat for Humanity

as a deep-pocket construction company, so some families did not make their payments which

is important to the Habitat formula, and other families became bitter because they were

making their payments, and they didn’t feel the ones who didn’t pay should be

allowed to do that.

Jim: Diana Moyers, a student of the U.S. International University, devoted many hours

to working as a volunteer with the community.

Diana: Until you build relationships with people you can’t expect them to become

committed to you and the projects that you think are good for them. You need to have them

be part of the planning process. You need to find out what their goals are, and if your

goals are different because of maybe a different knowledge that you have, then you need to

either educate them and work with them, or you need to go with what they want to do

because who are we from our country and what we know works in our country to come and tell

someone else in a different country how they should do things? That was my main point. I

wanted the community to become part of the planning process because if they were to become

part of the planning process, they would also become part of the doing process, and then

in the end, the end result would be theirs.

Jim: Out of the problem of the high water table, Skip has developed an innovative and

inexpensive wetlands water treatment that could find wider applications.

Skip: The entire sewage treatment system here consists of a collection system with 40

homes feeding a three compartment 15,000 gallon septic tank. The liquid from that enters

this plastic-lined gravel filter bed, which is the constructed wetlands portion. It takes

about a week to flow through. The bulrushes and cattails are helping to filter and bring

oxygen down for aerobic digestion, and what comes out at the end of that process is

comparable to secondary treated water in the U.S. with much more expensive plants.

That water can then be percolated into the ground, or, as we are trying to do here,

reclaiming it for irrigating fruit trees now and a whole park later.

Jim: And he has helped form WeCan University to address the issues of more sustainable

building and more community involvement.

Skip: The lesson from this, where do we go with the next project?, is to do a WeCan

University, eco-university, where everybody plans a project together, including the

families who will live in it, and they take a life and a responsibility and an ownership

of that project.

We formed WeCan, which is World Eco Community Action Network, and we use the acronym

WeCan for empowerment. That was formed primarily to help out with those goals, and its job

is to combine the talents of the academic universities and organizations, whether

government or non-government, and volunteer organizations like Habitat for Humanity, and

bring them together in a synergistic way. We have forums for experts providing their help,

and volunteers learning through experiential learning by getting their hands on, and

coming out and working with the people, not only learning the technology, but learning the

culture and reaching out.

I think the main lesson I learned was that the selection and education process is as

important, if not more important, than the building process, itself. As we did in Tijuana,

you can go build blitz homes and build them quickly and you’ll have structures and

that’s all, no spirit, and no sense of ownership by the occupants. However, as we

have learned a bit by the Tecate project, we hope to encompass in the WeCan University

philosophy, the families have to be involved in the process as if they were

owner-builders, and they are designing their homes with experts helping them, and they are

learning technologies to help their community succeed.

Jim: A more ecologically sane and sustainable way of living is not just for the less

developed nations of the world, but for all of us. Back at Earth Day Skip summed up the

direction we need to go in.

Skip: Americans tend to be paternalistic and think that we have all the solutions for

the rest of the world. I believe we can learn a lot from these people in the other worlds,

our neighbors, if we learn to respect them and know them one on one. I think housing

techniques, gardening techniques, their culture, the way they work together in community,

those are things that we can learn, so in a way Tecate is a staging base and learning

place for us, as well. The people who go down there come back with an appreciation for

recycling, for preserving resources that are precious down there, and hopefully that

lesson will be expanded and multiplied in the United States. We definitely need to

downsize and live more simply and closer to the earth. We have some advantages that we

should share. We have technology. We have photovoltaics, for example, solar electricity

that we can share, and we are learning about strawbale building, although that’s an

ancient technology, and we have a pretty strong movement in the western U.S. to develop

that, and it looks wonderful for Mexico and other countries, as well.

Many people around the world view America as streets paved with gold, and they are

striving to mimic us, and I think that’s a mistake. We need to tell them that we have

made mistakes, and we are turning around to learn from them how to live more simply and

basically. We need to not encourage mimicking our style of life.

I have two major goals with WeCan. One is to help other people in third world areas,

and in our areas that need help with housing and community development, but the other, and

maybe more subtle, is to effect our own lifestyle. As these students as the people who

participate in this program participate in an experiential way, they learn we don’t

need so much. They learn that they can empower themselves to do things for themselves, and

to live perhaps the most simple lifestyle that is more beautiful.